The most basic type of cheat code is one created by the game designers and hidden within the video game itself, that will cause any type of uncommon effect that is not part of the usual game mechanics. Cheat codes are usually activated by typing secret passwords or pressing controller buttons in a. The best and largest selection of PC game cheats, PC game codes, PC game cheat codes, PC cheatcodes, PC passwords, PC hints, PC tips, PC tricks, PC strategy guides, PC FAQs, codes for PC, pc codes, pc cheats, pc cheat codes, pc cheatcodes, pc passwords, pc hints, pc tips, pc tricks, pc strategy guides, pc faqs, pc video game cheat codes. Any player who suspects that the card discarded by a player do not match the rank called can challenge the play by calling 'Cheat!' Then the cards played by the challenged player are exposed and one of two things happens: 1. If they are all of the rank that was called, the challenge is false, and the challenger must pick up the whole discard pile. Chrome T-Rex game high score cheat. To access the T-Rex game, either turn off your internet connection and search something on Chrome or type chrome://dino in the address bar and hit Enter if you don’t want to go offline. Now right-click anywhere and select “Inspect” from the context menu. Here move to the “Console” tab and paste this code Runner.instance.setSpeed(1000) and press.

For most nongamers, the question of whether cheat codes equal cheating seems pretty simple. 'Cheating' means gaining an unfair advantage, after all, usually by breaking some kind of rule. So, yeah, a cheat code is cheating, because you're breaking a rule that others have to adhere to, right? Follows logic. But let's keep in mind that semantics might make a big difference here. What if we called them 'shortcuts' or even — as we might see — 'bugs'? Suddenly, we're not necessarily cheating — we're just taking advantage, instead of stealing an unfair advantage. So before we bang the gavel and declare cheat codes either cheating or fair play, let's discuss what a cheat code really is.

The traditional cheat code is one that you can enter while playing the game. To accomplish this, you either enter the code manually or execute a series of actions during gameplay. Either way, doing so will unlock something previously hidden in the game. This is where the 'cheat' part of cheat codes really comes into question.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The cheat itself could be lots of different things. Maybe the code gives you a shortcut around the playing field, or maybe it helps you get your hands on a useful tool without having to stumble upon it. It might just be a weird skill — maybe your character is suddenly able to digest gluten! (This idea comes from my most boring video game pitch, the 'Baking for Large Crowds Challenge.')

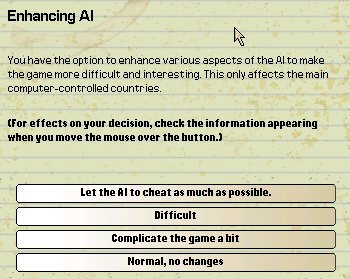

Now, it's important to note that not all of these cheats are accidental. Developers might build them in for a multitude of reasons. Some cheat codes actually make a game harder, which sounds crazy but is great for game developers looking to keep gamers involved by ramping up the challenge or competition. (In the 'Baking for Large Crowds Challenge,' that would probably mean giving half the people nut allergies and half the people high-protein diets.) But beyond simply doing it for fun, developers also sometimes design cheats to help them with testing. If they're working on a complicated, intricate game, they might need some quick ways to get to other levels or test for bugs in certain places. And, of course, there could just be a mistake in the code that allows a person to jump levels — but that would be pretty unusual with the quality-assurance processes these days.

In other words, a cheat isn't really the same as a hack, for instance, where a savvy developer (or just someone with programming knowledge) can edit or modify the code of the game to create shortcuts or automate tasks. And that might represent a big difference between what we think of as 'cheating' and what we think of as a competitive way to play the game.

So when we ask if cheat codes are cheating, the answer is a pretty strong maybe. Sure, gamers could be finding an advantage that the game makers didn't intend to include. But they might also be finding a more unique — or even challenging — way to play the game that's been built into the system. Or they might be doing a vague amalgamation of both — which means it's up to the player to decide if they're a cheater or a champion.

Advertisement

Related Articles

Sources

- McFerran, Damien. 'Code Red: The History of the Cheat.' Redbull.com. June 24, 2014. (May 13, 2015) http://www.redbull.com/us/en/games/stories/1331660993180/the-history-of-the-cheat-code

| Alternative names | Bluff, Bullshit, B.S., I Doubt It |

|---|---|

| Type | Shedding-type |

| Players | 2–6 |

| Skills required | Counting, number sequencing[1] |

| Age range | 8+[2] |

| Cards | 52 (104) |

| Deck | French |

| Play | Clockwise |

| Random chance | Medium[1] |

| Related games | |

| Valepaska, Verish' Ne Verish', Poker Bull | |

| Easy to play | |

Cheat (also known as Bullshit, B.S., Bluff, or I Doubt It[3]) is a card game where the players aim to get rid of all of their cards.[4][5] It is a game of deception, with cards being played face-down and players being permitted to lie about the cards they have played. A challenge is usually made by players calling out the name of the game, and the loser of a challenge has to pick up every card played so far. Cheat is classed as a party game.[4] As with many card games, cheat has an oral tradition and so people are taught the game under different names.

Rules[edit]

One pack of 52 cards is used for four or fewer players; five or more players should combine two 52-card packs. Shuffle the cards and deal them as evenly as possible among the players. No cards should be left. Some players may end up with one card more or less than other players. Players may look at their hands.

A player's turn consists of discarding one or more cards face down, and calling out their rank - which may be a lie.[6]

The player who sits to the left of the dealer (clockwise) takes the first turn, and must call aces. The second player does the same, and must call twos. Play continues like this, increasing rank each time, with aces following kings.[6]

If any player thinks another player is lying, they can call the player out by shouting 'Cheat' (or 'Bluff', 'I doubt it', etc.), and the cards in question are revealed to all players. If the accused player was indeed lying, they have to take the whole pile of cards into their hand. If the player was not lying, the caller must take the pile into their hand. Once the next player has placed cards, however, it is too late to call out any previous players.[6]

The game ends when any player runs out of cards, at which point they win.

Variants[edit]

- A common British variant allows a player to pass their turn if they don’t wish to lie or if all the cards of the required rank have clearly been previously played.

- Some variants allow a rank above or below the previous rank to be called.[6] Others allow the current rank to be repeated or progress down through ranks instead of up.[6]

- Some variants allow only a single card to be discarded during a turn.

- In some variations a player may also lie about the number of cards they are playing, if they feel confident that other players will not notice the discrepancy. This is challenged and revealed in the usual manner.[6]

- In another variant, players must continue placing cards of the same rank until someone calls 'Cheat' or everyone decides to pass a turn.

International variants[edit]

The game is commonly known as 'Cheat' in Britain and 'Bullshit' in the United States.[6]

Mogeln[edit]

The German and Austrian variant is for four or more players and is variously known as Mogeln ('cheat'), Schwindeln ('swindle'), Lügen ('lie') or Zweifeln ('doubting').[7] A 52-card pack is used (two packs with more players) and each player is dealt the same number of cards, any surplus being dealt face down to the table. The player who has the Ace of Hearts leads by placing it face down on the table (on the surplus cards if any). The player to the left follows and names his discard as the Two of Hearts and so on up to the King. Then the next suit is started. Any player may play a card other than the correct one in the sequence, but if his opponents suspect him of cheating, they call gemogelt! ('cheated!'). The card is checked and if it is the wrong card, the offending player has to pick up the entire stack. If it is the right card, the challenger has to pick up the stack. The winner is the first to shed all their cards; the loser is the last one left holding any cards.[8]

Verish' Ne Verish'[edit]

The Russian game Verish' Ne Verish' ('Trust, don't trust') - described by David Parlett as 'an ingenious cross between Cheat and Old Maid'[9] - is also known as Russian Bluff, Chinese Bluff or simply as Cheat.

The game is played with 36 cards (two or three player) or 52 (four or more). One card is removed at random before the game and set aside face-down, and the remainder are dealt between players (even if this results in players having differently sized hands of cards).[9]

The core of the game is played in the same manner as Cheat, except that the rank does not change as play proceeds around the table: every player must call the same rank.[9]

Whenever players pick up cards due to a bluff being called, they may – if they wish – reveal four of the same rank from their hand, and discard them.[10]

In some variants, if the player does not have any of the rank in their hand, they may call 'skip' or 'pass' and the next player takes their turn. If every player passes, the cards on the table are removed from the game, and the last player begins the next round.[citation needed]

Canadian/Spanish Bluff[edit]

Similar to Russian Bluff, it is a version used by at least some in Canada and known in Spain. The rules are rather strict and, while a variation, is not open to much variation. It is also known in English as Fourshit (single deck) and Eightshit (double deck), the game involves a few important changes to the standard rules. Usually two decks are used[6] instead of one so that there are 8 of every card as well as four jokers (Jokers are optional), though one deck may be used if desired. Not all ranks are used; the players can arbitrarily choose which ranks to use in the deck and, if using two decks, should use one card for each player plus two or three more. Four players may choose to use 6,8,10,J,Q,K,A or may just as easily choose 2,4,5,6,7,9,J,K, or any other cards. This can be a useful way to make use of decks with missing cards as those ranks can be removed. The four jokers are considered wild and may represent any card in the game.

The first player can be chosen by any means.[11] The Spanish variation calls for a bidding war to see who has the most of the highest card. The winner of the challenge is the first player. In Canada, a version is the first player to be dealt a Jack face up, and then the cards are re dealt face down.

The first player will make a 'claim' of any rank of cards and an amount of their choice. In this version each player in turn must play as many cards as they wish of the same rank.[6] The rank played never goes up, down nor changes in any way. If the first player plays kings, all subsequent players must also play kings for that round (it is non-incremental). Jokers represent the card of the rank being played in each round, and allow a legal claim of up to 11 of one card (seven naturals and four jokers).[12] A player may play more cards than they claim to play though hiding cards under the table or up the sleeve is not allowed. After any challenge, the winner begins a new round by making a claim of any amount of any card rank.

If at any point a player picks up cards and has all eight natural cards of a certain rank, he declares this out loud and removes them from the game. If a player fails to do this and later leads a round with this rank, he or she automatically loses the game.

Once a player has played all his or her cards, he or she is out of that particular hand. Play continues until there are only two players (at which point some cards have probably been removed from the game). The players continue playing until there is a loser. The object of the game is not so much to win, but not be the loser. The loser is usually penalised by the winners either in having the dishonour of losing, or having to perform a forfeit.

China/Iranian Bullshit[edit]

In the Fujian province, a version of the game known as 吹牛 ('bragging') or 说谎 ('lying') is played with no restriction on the rank that may be called each turn, and simply requiring that each set is claimed to be of the same number.

On any given turn, a player may 'pass' instead of playing. If all players pass consecutively, then the face-down stack of played cards is taken out of the game until the next bluff is called. The player who previously called a rank then begins play again. [6]

This version, also sometimes called Iranian Bullshit,[13] is often played with several decks shuffled together, allowing players to play (or claim to play) large numbers of cards of the same rank.[6]

Sweden[edit]

Known as bluffstopp (a portmanteau of bluff ('bluff') and stoppspel ('shedding game'.)) Players are given six (or seven) cards at the start of the game, and the remainder makes a pile. Players are restricted to follow suit, and play a higher rank, but are allowed to bluff. If a player is revealed to be bluffing, or a player fails to call or a bluff, the player draws three cards from the pile.

Additional rules and players to play more than one card in secret, and drop cards in their lap. But if this is discovered, the player must draw three or even six cards.

References[edit]

- ^ abChildren's Card Games by USPC Co. Retrieved 22 April 2019

- ^Kartenspiele für Kinder - Beschäftigung für Schmuddelwetter at www.vaterfreuden.de. Retrieved 23 April 2019

- ^Guide to games: Discarding games: How to play cheat, The Guardian, 22 November 2008, [1] retrieved 28 March 2011

- ^ abThe Pan Book of Card Games, p288, PAN, 1960 (second edition), Hubert Phillips

- ^The Oxford A-Z of Card Games, David Parlett, Oxford University Press, ISBN0-19-860870-5

- ^ abcdefghijk'Rules of Card Games: Bullshit / Cheat / I Doubt It'. Pagat.com. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^Geiser 2004, p. 48. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGeiser2004 (help)

- ^Gööck 1967, p. 31. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGööck1967 (help)

- ^ abcParlett, David (2000). The Penguin encyclopedia of card games (New ed.). Penguin. ISBN0140280324.

- ^'Rules of Card Games: Verish' ne verish''. Pagat.com. 17 November 1996. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^'Dupyup.com'. Dupyup.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^'Bullshit, the Card Game'. Khopesh.tripod.com. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^'Board Games'. The Swamps of Jersey. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

Should I Cheat

Further reading[edit]

- Geiser, Remigius (2004). '100 Kartenspiele des Landes Salzburg', in Talon, Issue 13.

- Gööck, Roland (1967). Freude am Kartenspiel, Bertelsmann, Gütersloh.

- Albert Morehead (1996). Official Rules of Card Games. Ballantine Books. ISBN0-449-91158-6.

- USPC Card Game Rule Archive (under the name 'I Doubt It') accessed on 2006-05-10.